All about blood

Blood is unique among all the body’s tissues in that it is the only fluid tissue. By way of the body’s network of blood vessels, blood transports everything that has to be carried from one place to another within the body, such as:

- oxygen to tissues throughout the entire body;

- waste products to the excretory organs such as the kidneys, liver and lungs, which then eliminate them;

- antibodies and white blood cells to the sites where they are needed to fight infection; and

- heat from inner parts of the body to the skin to keep body temperature stable.

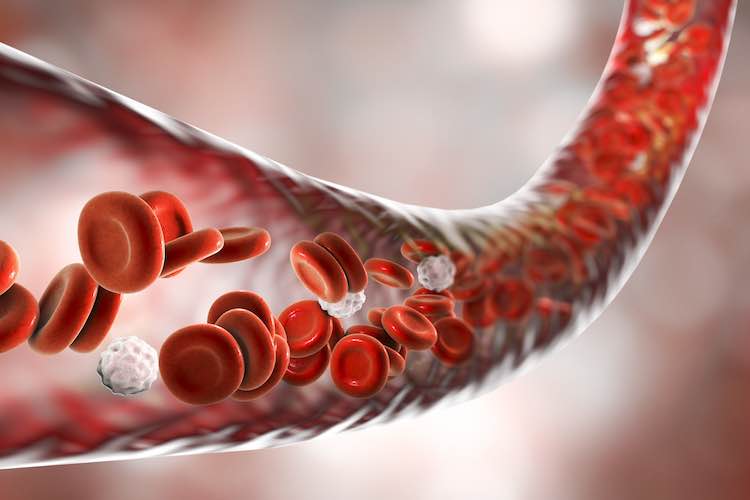

Blood comprises about 8 per cent of a person’s body weight, it is about 5 times thicker than water, and in a normal-sized adult, there are about 5 litres of it. What we understand as ‘blood’ is not a single substance, but a suspension of several components, all of which have different functions, held together in a straw-coloured fluid called plasma.

The components

- Red blood cells: These are produced in the bone marrow. They contain haemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying pigment in the blood, and hence they allow oxygen to be transported to the cells of the body. In a healthy person, each millilitre of blood contains about 5 billion red blood cells.

- White blood cells (leucocytes): These are part of the body’s defence system. When they detect a foreign substance such as a virus, white blood cells flock to the site of infection or damage. Some white cells, such as neutrophils, work by surrounding and then destroying viruses or bacteria, whereas others (lymphocytes) work by producing chemicals (antibodies) which build up the body’s resistance to disease. People have fewer white cells than red; a healthy person will have about 7 million white blood cells per millilitre of their blood.

- Platelets: These are also produced in the bone marrow. Their job is to help clot blood and seal wounds after injuries. There are about 250 million platelets in a millilitre of blood.

- Plasma: This is the clear, yellowish fluid left after everything else has been removed. It consists of about 70 per cent water plus minerals such as calcium, sodium and potassium, and a range of vital proteins such as transport proteins, clotting factors, and albumin. It transports carbohydrates, fats, hormones and antibodies, and also transports waste products to the kidneys where they are excreted.

The heart usually pumps all the blood around the body in about one minute or so in a person who is resting.

Bleeding

Normally, blood flows smoothly through the blood vessels, but if a blood vessel wall is damaged or breaks, blood leaks out, causing bleeding. When this occurs, a series of chemical reactions comes into play to stop the bleeding and prevent further damage. Basically, this process occurs as follows.

- Platelets stick to the site of injury, helping to form an initial ‘plug’. Just by this process alone, platelets can stop blood loss from small blood vessels.

- Chemicals known as clotting activators are released from damaged tissue cells and from platelets themselves.

- Through a series of chemical reactions in the blood, a protein known as fibrin is formed.

- Fibrin forms a mesh-like network of threads across the wound.

- Platelets, red blood cells and other blood components become trapped in this mesh — the whole lot clumps together and forms a clot, which helps stop further bleeding.

Internal bleeding

Inflammation, infection, an ulcer or a tumour may cause damage to internal blood vessels, resulting in bleeding. Bleeding from the digestive tract may make vomit or faeces appear darker than usual because the blood is partially digested. Sometimes internal bleeding is not discovered until severe anaemia develops (where the red blood cells do not provide enough oxygen to body tissues, leading to symptoms such as tiredness, pale skin and weakness).

Except for the occasional nosebleed and menstruation, bleeding that is not caused by injury usually requires medical investigation. Menstrual blood loss, if it is very heavy or frequent, can lead to anaemia. This, however, can often be corrected by eating a diet high in green, leafy vegetables and red meat and/or taking a course of iron supplements.

Bleeding disorders

Sometimes the mechanisms that stop bleeding develop defects. As a result, some people start bleeding even without any injury, or experience abnormally prolonged and excessive bleeding after an injury. For them, vital processes such as clotting (for example, in haemophilia, a condition where the body lacks an important clotting factor), or plugging of damaged blood vessels by platelets (in thrombocytopenia, a condition in which there is an abnormally low level of platelets in the blood) are either compromised or do not function.

Coagulation defects may be congenital (present from birth) or acquired later in life. Depending on the condition, treatment for bleeding disorders may include transfusions of fresh frozen plasma or platelets, or injections of the missing coagulation factor or factors (enzymes vital for blood clotting).