Hepatitis B is a serious liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus. ‘Hepatitis’ means inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B infection starts as an acute (short-lived) infection, and in most people it will clear in a few months. However, in some people the viral infection persists in the body, and it can go on to be chronic (long-term).

Chronic hepatitis B can result in complications such as cirrhosis (liver scarring), liver failure and liver cancer.

How do you get hepatitis B?

Hepatitis B is found in the body fluids (such as blood, saliva, semen and vaginal secretions) of people with acute and chronic hepatitis B. Hepatitis B is very infectious and can be transmitted in a number of different ways, including through:

- unprotected sexual contact, including oral sex;

- a bite from an infected person;

- mother-to-newborn infection during childbirth;

- unscreened or improperly screened blood or blood products;

- sharing contaminated drug injecting equipment;

- using non-sterile, contaminated instruments, for example in body-piercing, tattooing or acupuncture; and, to a lesser extent,

- sharing personal items that could break the skin (such as toothbrushes or razors) and household contact (for example contact between children with open sores).

People with chronic hepatitis B may feel well and have no symptoms, but can pass on hepatitis B to others. The hepatitis B virus can survive for up to a week outside the body.

How common is hepatitis B infection?

Approximately 1 in 100 Australians are infected with hepatitis B, but this figure is higher in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and in Australians born overseas.

Hepatitis B carrier rates are high in the African and Western Pacific regions, where approximately 6 per cent of the adult population is infected. Carrier rates are lower and between one and 3 per cent in parts of the Eastern Mediterranean countries, South-east Asia, and European populations. Rates are low (less than one per cent) in the US, northern Europe and New Zealand.

Hepatitis B symptoms

Many people don’t have symptoms of acute (new) hepatitis B infection, but if they do, symptoms usually develop about 3 months after being infected with the virus. Symptoms may include:

- fever (temperature of 37.5 /38 degrees Celsius or above);

- jaundice (a yellowish discoloration of the eyes and skin);

- pale stools and dark urine;

- tiredness;

- reduced appetite;

- nausea and vomiting;

- abdominal pain or discomfort (especially in the upper right region of the abdomen);

- skin rash; and

- joint and muscle pain.

Most infants and young children experience no symptoms, and only about 30 to 50 per cent of adults experience symptoms of hepatitis B. People who have not experienced any symptoms may not be aware that they have been infected, and may unknowingly pass the infection on to others. Being free of symptoms does not mean you are not infectious. You may not have symptoms, but you can still transmit the virus to other people.

If you have acute hepatitis B infection and your body clears the virus after a few months, you will become immune to further infection with hepatitis B. You also won’t be infectious to other people.

However, some people who develop chronic hepatitis B can go up to 20 to 30 years without experiencing any symptoms, and there is a risk they infect others.

Tests and diagnosis

If your doctor suspects you have hepatitis B, they will ask about any symptoms and risk factors for hepatitis B that you may have, and perform a physical examination.

A blood test is needed to diagnose hepatitis B infection. The blood test can help determine whether you have a new (acute) or ongoing (chronic) hepatitis B infection, or have been infected in the past, but have now cleared the virus. A sample of your blood, taken from a vein in your arm may be tested for:

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) – this is part of the outer surface of the virus. It indicates either a new infection (symptoms may not have occurred yet) – or an ongoing (chronic) infection – either way you could infect another person;

- Hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) – a positive reaction to this shows that you have been exposed to hepatitis B, either by a previous infection or by successful vaccination. The virus is not present anymore, and you are not infectious. You are protected from any future infection.

- Hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) – antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen. This is found in hepatitis B carriers as well as people who have cleared the hepatitis B infection. It usually stays for life. It is negative in people who have been vaccinated, but positive in people who have had a past infection. It doesn’t provide any protection against infection.

If you are diagnosed with acute hepatitis B, your family members, household contacts and sexual partners will be offered testing and vaccination if required.

New cases of hepatitis B are a notifiable disease across Australia.

If you are diagnosed with acute hepatitis B, liver function tests may be needed to monitor for any adverse effects on your liver. Liver function tests are a group of tests carried out together on a blood sample, which can help diagnose inflammation and damage to the liver. They may be used to assess the extent of any damage caused by hepatitis B. ALT (alanine aminotransferase or alanine transaminase) is one liver function test that is raised when the liver is inflamed, including due to hepatitis B.

FibroScan is a special type of ultrasound which can measure the stiffness or ‘hardness’ of the liver. The more fibrosis or scarring of the liver, the higher the stiffness reading will be. This is useful as it can help your doctor assess the degree of liver damage that has occurred.

Acute hepatitis B infection

Most adults (95 per cent) who have been infected with hepatitis B virus recover completely, clearing the virus from their bodies within 6 months without any specific treatment.

Rarely, a person may develop fulminant hepatitis or liver failure from acute hepatitis B infection. If this happens, they will need medicines and possibly a liver transplant.

If you have acute hepatitis B, vaccination against hepatitis B may be suggested for your sexual contacts, family members and close contacts.

Infants and children infected with hepatitis B rarely experience any symptoms of acute infection, but are at high risk of developing chronic hepatitis B infection.

Acute hepatitis B treatment

If you are in the early stages of hepatitis B infection, you may only need supportive care to help your body fight the infection. This includes drinking sufficient water and fluids to ensure that you are not dehydrated. Keep healthy by not smoking, avoid alcohol and eat a healthy, varied diet. Make sure you exercise, get enough rest and keep a healthy body weight. Do not take illicit drugs.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is an emergency option that can be offered if you have only just been exposed to the hepatitis B virus. PEP is given to lower your chances of hepatitis B infection developing. This might apply if, say, you had a needlestick injury or a bite from an infected person.

PEP for hepatitis B should be done within 72 hours of exposure, but ideally in the first 24 hours. You will be tested to see if you have any immunity to hepatitis B – from previous vaccination or infection. If you have no immunity, PEP involves one injection of immunoglobulin, followed by 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine over the next 6 months.

You will be tested to see if you have developed hepatitis B at intervals in the window period, which lasts 6 months. Only after 6 months can doctors be sure that you won’t develop an infection.

PEP for hepatitis B is generally available from hospital emergency departments and sexual health clinics. PEP for hepatitis B infection will not protect you from other bloodborne viruses such as HIV or hepatitis C, which have different PEP processes.

Chronic hepatitis B infection

If after 6 months, follow-up blood tests show evidence of ongoing infection with hepatitis B, then your body has not cleared the virus, and you are said to have chronic hepatitis B. It is estimated that almost half of Australians with chronic hepatitis B have not been diagnosed.

It’s usually infants and young children who are unable to clear the virus from their bodies, and develop a chronic, or long-term, infection:

- of infants, 90 per cent will become chronically infected.

- 30% of children will develop lifelong (chronic) infection.

- fewer than 5 per cent of adults or adolescents will be chronically infected and have the hepatitis B virus infection for life.

The risk of persistent (chronic) infection is higher in adults if their immune system is not working properly and can’t fight off the virus. Being a chronic carrier of hepatitis B infection may eventually lead to liver cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Of the millions of people worldwide who are chronically infected with hepatitis B, many live in the Asia-Pacific region. More than 232,000 people in Australia have chronic hepatitis B infection.

Most of the people in Australia with chronic hepatitis B infection were born overseas, in countries with high rates of hepatitis B infection. In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, there are also higher rates of chronic hepatitis B infection.

Chronic hepatitis B infection can result in complications such as fibrosis (the first stage of scarring) or cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer and liver failure. Without adequate treatment and monitoring, these complications can occur – and there are no warning signs.

Chronic hepatitis B treatment

Treatment is not always required for people with chronic hepatitis B infection. Some people may need treatment, but treatment will not cure them of the virus. The aim of treatment is to suppress the hepatitis B virus in the body, until it is virtually undetectable, which can stop the progression of liver disease and prevent liver cancer. Unlike hepatitis C, there is no cure for hepatitis B at the moment.

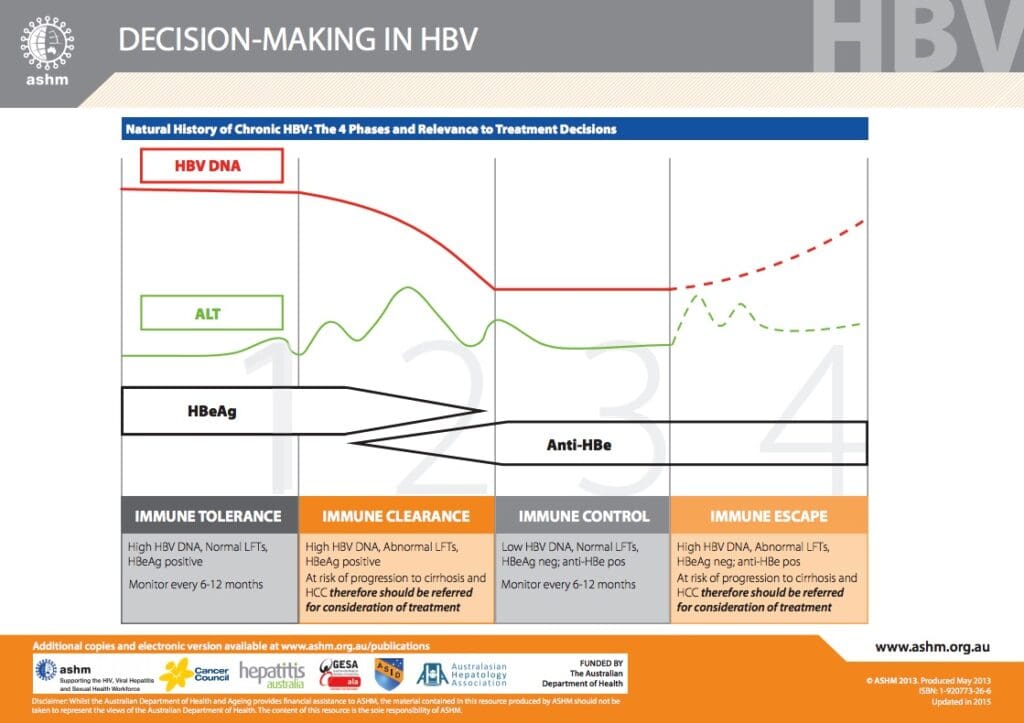

Once diagnosed, the doctors will try to identify what phase of infection you are at (there are 4 phases). This determines how much ongoing damage is happening to your liver and so whether you will benefit from treatment.

While many people with chronic hepatitis B do not need treatment, everyone with chronic hepatitis B needs regular monitoring. And because they are carriers of the virus, people with chronic hepatitis B can infect other people.

To determine whether a person with chronic hepatitis B infection should have treatment, they will need tests to assess the stage of their disease. Then the doctor will advise ongoing monitoring for the rest of their life, usually every 6 months.

Regular monitoring like this will tell the doctor if the virus is active. If the virus becomes active, you will need to start taking treatment to keep the virus under control and protect your liver from damage.

Testing in chronic hepatitis B

Testing in chronic hepatitis B is complicated but can involve:

- Viral load: The amount of hepatitis B virus in the blood — known as the viral load — helps determine the likelihood of developing complications. Your HBV viral load is measured by a blood test that measures the level of HBV DNA – the genetic material of the virus. Higher viral loads mean the virus is multiplying and are associated with an increased risk of developing cirrhosis and cancer of the liver, so keeping the viral load as low as possible can help reduce or prevent injury to the liver.

- Liver function tests: This blood test can show if there is any damage to your liver by measuring specific enzymes and chemicals, particularly ALT (alanine aminotransferase) levels.

- Hepatitis B e antigen status (HBeAg and anti-HBe): HBeAg is a hepatitis B envelope protein and is found early in acute HBV infection – it means the virus is active. Anti-HBe is antibody to the HBe protein and indicates lower infectivity and that the virus is not active.

- FibroScan: This is a scan of your liver to show the extent of any scarring. It is similar to an ultrasound and is done on the outside of your body. FibroScan is painless and is used as an alternative to a liver biopsy. FibroScan gives a score for the stiffness of your liver, which correlates to the degree of fibrosis or cirrhosis. The higher the score, the more damaged your liver is.

There are many people currently living in Australia with chronic hepatitis B who are either not being treated or not being monitored and face an increased risk of complications and death from their disease. If you have chronic hepatitis B infection, see your doctor who can advise how to manage your condition.

Phases of chronic hepatitis B infection

Decision-Making in HBV ©ASHM 2015

Medicines for chronic hepatitis B

There are 2 types of medicines for chronic hepatitis B. Both types are prescription medicines, and examples of both types of medicine are available on the PBS. General Practitioners in Australia are now able to prescribe some of these medicines.

Which type of medicine you are prescribed will depend on many factors, including how much damage your liver may or may not have already sustained and whether or not you are pregnant. It is not yet possible to permanently remove the hepatitis B virus, so the aim of current treatments is to suppress the virus and prevent any further liver damage. There are treatments to prevent an unborn baby from getting hepatitis B from its mother.

Antiviral treatment is used to stop the hepatitis B virus from replicating in your cells and reduce the amount of hepatitis virus in the blood. Medicines such as entecavir (e.g. Baraclude), tenofovir (e.g. Vemlidy, Viread), lamivudine (e.g. Zeffix) and adefovir (e.g. Hepsera) are usually taken for the long term.

Some people with hepatitis B will need to take medicines for the rest of their life. They are usually taken every day as a tablet. Sometimes a combination of antivirals is given. Antiviral medicines can reduce the risk of liver damage getting worse, reduce the risk of liver cancer, and even sometimes reverse liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. These medicines mostly have no side effects, but resistance to the medicines can emerge. If resistance to the medicines occurs, or you do have troublesome side-effects, your doctor may suggest another antiviral.

Pegylated interferons are medicines that work on the immune system to help it fight infection. Pegylated interferons are synthetic versions of interferons – molecules produced naturally by the immune system to fight viral infections and stop viruses from multiplying.

Pegylated interferon is longer acting than other interferons, allowing once-weekly dosage, and so has largely replaced other interferons in the treatment of hepatitis B.

Pegylated interferon alfa-2a (e.g. brand name Pegasys) is usually given by weekly injection under the skin for nearly a year. Pegylated interferon is not usually suitable for pregnant women or women wanting to get pregnant. Resistance does not develop to interferons, but they are more likely to cause side-effects than antivirals.

Liver transplant

If there is severe damage to the liver and /or liver failure, some of the treatment options may not be suitable, and a person may be evaluated for a liver transplant. Liver transplantation will not cure a person of hepatitis B – as the virus will still be in the blood and can re-infect the new liver. Not everyone is suitable for a liver transplant – people are carefully screened. Factors such as age, general health and alcohol and drug use are taken into consideration. Only a small number of liver transplants are carried out each year in Australia – 318 were done in 2018.

Living with chronic hepatitis B

Aside from regular blood tests and check-ups with your doctor, there are other things you can do to reduce your chance of developing liver damage if you have chronic hepatitis B. These include avoiding alcohol use and not smoking. Eat a healthy diet, exercise regularly and get enough sleep.

Co-infection with another virus, such as HIV or Hepatitis C, makes treatment more complicated and increases the likelihood of you developing liver damage.

Take any medicines prescribed as directed and have regular blood tests to monitor for any signs of resistance to the medicines.

Protecting other people

If you have chronic hepatitis B, everyone in your family, your sexual partners, and people you live with should have a hepatitis B test, and they may be offered free vaccination.

If you share needles with anyone who is not vaccinated against hepatitis B, they should see a doctor straight away as they may need immunoglobulin. Similarly, if you have unprotected sex with someone who is not vaccinated or immune, they should see a doctor immediately.

Hepatitis B is a contagious disease and a sexually transmitted disease, and vaccination is the best way to protect against it. The hepatitis B vaccine is part of the routine childhood immunisation schedule in Australia now.

If you have chronic hepatitis B and you are pregnant, your baby can be protected against the virus by being vaccinated and given hepatitis B immunoglobulin within 12 hours of being born. They will then also need follow-up vaccines like other infants and children.

If you are HBsAg-positive, that means you are positive for the surface antigen and have an active infection, and can infect other people with hepatitis B.

Which doctors treat hepatitis B?

If you have hepatitis B you may be looked after by your general practitioner, a gastroenterologist or a hepatologist (liver specialist).

Hepatitis B vaccination in Australia

The most effective way of preventing the spread of hepatitis B is through vaccination. All children are eligible for free vaccination in Australia.

The National Immunisation Program Schedule recommends that the first hepatitis B vaccination is given at birth. Three further doses are then administered at 2, 4, and 6 months of age. These are given in combination with other routine immunisations, so that no additional jabs are required. Immunity from hepatitis B vaccination is long lasting.

Catch-up vaccination is recommended for children 10 years of age or older who have missed being vaccinated. Hepatitis B catch-up vaccination is free to 10-19 year-olds on the National Immunisation Program.

Vaccination is also recommended for adults who are at increased risk of hepatitis B infection and those at increased risk of severe disease, including:

- people who are immunocompromised such as people with HIV and people on haemodialysis;

- people with chronic liver disease and/or hepatitis C who are not immune;

- people who may be exposed to the virus as a result of their occupation (such as medical, dental or laboratory healthcare workers and emergency services personnel);

- people with developmental disabilities who attend daycare facilities;

- inmates and staff of correctional facilities who are not immune;

- people who inject drugs;

- sex industry workers,

- people with certain blood disorders;

- transplant recipients who are not immune;

- people who are household or close contacts of a person with hepatitis B;

- people at risk of contracting the disease through sex with an infected person;

- travellers to countries where there are intermediate or high rates of hepatitis B infection.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are recommended to get tested and then be vaccinated as necessary. As are migrants from countries where there are high rates of hepatitis B infection (including East and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific Islands);

If you are unsure whether you have been vaccinated or have been previously exposed to hepatitis B, ask your doctor about having a blood test to check for antibodies to the virus.

Side-effects of hepatitis B vaccination

Most people don’t get side effects from hepatitis B vaccination, but possible side effects are soreness around the injection area, low-grade fever and aches. However, the risks of side effects from vaccination are generally much lower than the risk of not being immunised and of catching hepatitis B – as it is a serious disease with potentially life-threatening consequences. You can’t catch hepatitis B from the vaccination. Both the primary vaccine (including the birth dose) and booster vaccines are well tolerated.

Travel vaccination for hepatitis B

Hepatitis B vaccination is not required for travel to any country; however, it would be wise to have it in certain circumstances. Your doctor or travel vaccination centre will be able to advise you according to your particular destination and circumstances.

Vaccination is recommended for travellers in these circumstances:

any person travelling to regions of intermediate or high levels of endemic hepatitis B virus transmission, and either:

- travelling for a long-term visit or for frequent short visits; or

- likely to participate in activities that increase their risk of exposure to hepatitis B virus.

Activities that might increase risk of exposure include:

- doing healthcare work (e.g. medical, dental or laboratory) where the activities might result in blood exposure;

- having intimate sexual contact with the local population;

- having a tattoo or body piercing; or

- having invasive medical, dental, or other treatment in local facilities during the stay.

Ideally, immunisation should begin 6 months before travel to allow time to complete the full series of vaccinations. There are usually 2 or 3 doses, with the last dose given 6 months after the first dose.

For people with limited time before departure who are at imminent risk of exposure, there is an accelerated schedule available for either hepatitis B alone (Engerix-B) or for combined hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination (Twinrix). This accelerated course of vaccinations includes injections at 0, 7 and 21 days, with a booster dose necessary at 12 months.